Alexander Trocchi

by Andrew Hodgson

Much is written of Alexander Trocchi’s “profound nihilism”. It is often argued that in his rejection and modification of language and narrative; work and reality (through taking heroin): he “willed death”; “willed to nothingness”. In his “serious novels” Young Adam (1954) and Cain’s Book (1960) amongst the detachment from other people; death; productive work; environment and the running maxims of disintegration of everything within and without the text; a nihilistic bent seems clear. But to reduce Trocchi to “disintegratory nihilist” seems to limit interpretation of his texts to type: the etchings of a death-wish junkie. I here set out to question this limitation.

Trocchi is shrouded in a vague anecdotal mythology. Born in Glasgow in 1925 and dying of pneumonia in London in 1984: the accepted narrative runs that he was a promising, brilliant writer and thinker in youth before falling into a morass of heroin and incoherency later on. Where once he was regarded as “the most prepossessing and talented writer on the scene”; destined to become his “generation’s Joyce” he became a hollow figure concerned only with the “ultra-hip”; the term in this context describes Trocchi pimping out his own wife. It appears he shifted from explorer and interpreter of sub-culture to being imprisoned by it. Around the time of Cain’s Book he began to no longer strive to create but consume. It would be a model Trocchi himself would agree with; from brother Adam to brother Cain. The two novels bookending some kind of irredeemable moment when he was made or made himself “a monster”. The legends that surround Trocchi as Cain are horrifying and unreal yet apparently true, getting everyone and anyone addicted to heroin, begging and stealing from friends; these could be termed the actions of a self-professed monster. But to put this all down to heroin seems to limit Trocchi’s inhumanity, he did after all abandon a wife and two young daughters to move to Paris to write Young Adam, and so perhaps this fall from grace is insincere; indeed a myth. His behaviour from Adam to Cain appears relatively unchanged; and so whether it is a nihilist or something else he spent his life becoming it certainly can’t be essentially termed a junkie. Even in Cain’s Book, Trocchi’s projection on the page seems outside the hell of junkie life, away from the busts, overdoses, deaths, addiction; his habit seems almost leisurely. As he drifts, just off the milieu; observing.

It is this calm and distant tone that makes me question the generic sorting of Trocchi into a tradition with the hallucinatory histrionics of Burroughs and “CHOOSE COKE”. Trocchi is more in the vein of Thomas De Quincey. Like De Quincey, Trocchi’s “inner-spacewalks” sapped him of whatever spark it was that his contemporaries so admired. Both quickly lost the will or ability to write. The parallels between Confessions of an English Opium Eater and Cain’s Book of a writer straddling the realms of coherence and incoherence are apparent. Yet the borderlands they inhabit are starkly different.

While De Quincey establishes a cosy norm to be usurped, the drifting scow of

Cain’s Book speaks of total detachment from the phenomenal world; a detachment apparent as early as

Young Adam.

The novel begins with the rejection of an authentic “I”; like Beckett’s godless Cartesian non-

cogito; the “I” for Trocchi can point to a space. In the form sketched here:

If a wall little by little exhibited cracks that might be taken to be the shape of the words “I am dying,” we might read the series of marks as words forming an intelligible sentence and yet not on that account suppose that the “I” refers to a person […] Certainly, we may see them simply as cracks that resemble writing and not take them to have meaning or to refer to anyone. Or we may, on the contrary read a message in them, and this would mean that we think the wall is speaking or that a spirit is using the wall in an attempt to communicate something to us.

From this we might better understand the “I” of Trocchi’s narratives as “arbitrary” and containing “its own inadequacy and its own contradiction”. It is a single crack in the façade of Young Adam’s fiction through which Trocchi “the spirit” communicates with us. This “I” here does not indicate a cogito inherent in the text but lack of it. It is the arbitrary subject of drift amongst the labyrinth of black lines on white paper; urban object on blank land, a paradoxical meeting of Trocchi’s self and his protagonist’s non-self; it is an idealist’s detachment from commodification of the novel. As Trocchi writes:

There was no intimate connection between my eye and a plant on the windowsill or between my eye and the woman to whom I was about to make love

In the act of observing Joe Taylor (Alex Trocchi) objectifies the phenomenal universe and though feeling its “hypnotising” force, feels a distance between the observer and the flatness of the distant objects; the flatness of the ink on the page; a two dimensional reality.

The flatness of Trocchi’s reality creates an ambiguous sense of confusion by his second “serious” novel. In Cain’s Book the slippage between author and protagonist has advanced to a state of total aporia; slipping between fact and fiction; space and time. In his own words, Trocchi is

stumbling across tundras of unmeaning, planting words like bloody flags in my wake. Loose ends, things unrelated, shifts, night journeys, cities arrived at and left, meetings, desertions, betrayals, all manner of unions, triumphs and defeats.

Though his assertion of this as an adopted aesthetic seems itself constructed. Trocchi is at the striking point of Situationist drifting yet it seems not developed by his heroin use but a by-product; what had for others been an adopted aesthetic has become Alexander Trocchi’s entire schema of perception. Here the space created by self-contradiction in Trocchi’s narratives; the “I” of his writing is not pointing to a void, or the inauthenticity of any reality whatsoever, but the hallucinatory delirium of the flowing together of “Scots” Alex and his narrator “Scots” Joe; the melting together of factual and fictional experience. For example in Cain’s Book:

I spoke of her thick white legs and I was aware of being inexact at the time, for of course she was wearing jeans. As she hung up the clothes she stood on the balls of her feet, foot, I should say, for she had only one leg.

This passage would not seem alien if present in Beckett’s First Love or any of his ‘Texts for Nothing’; however it does not point to a nothing at the heart of the text; it is not an oblique mirror. It is mimetic of the thoughts of a long-term heroin user. Of the aforementioned slippage between subjects; times; places; people; far from nothing it indicates a fractured everything. In this episode of Cain’s Book protagonist Necchi notices the two-legged-one-legged-woman alone on her scow as her husband goes off to the city. He heads over to her barge tied up alongside his and a dozen or so others and, it is implied, has sex with her. Soon after she disappears off back to her “folks’ house”, as if with his potency Necchi has awoken in her a dissatisfaction with her life on the barges. This situation is directly lifted from Trocchi’s own life; as he recounts to Allen Ginsburg some years later:

AT: Do you remember Mel Sabrum (?)

AG: The name I remember.

AT: He had this one-legged girl? Beautiful! -That’s the one-legged girl I refer to in Cain’s Book

AG: Ah ha.

AT: Oh, she was beautiful. I fell in love with her, you know..But, shit, we went to bed and I couldn’t get a fuckin’ hard-on! Now if I had got a hard-on that night, my whole life maybe would have been changed (and so would hers). But not being able to get it up? I suppose I couldn’t because I felt like I was betraying Mel.

And then about 6 months later she was dead

AG: Of what?

AT: Overdose.

And six months later Mel gave himself an overdose in the bath, Brooklyn, his mother’s flat

AG: Suicide?

AT: Yeah..Mel did it absolutely consciously.

I loved that lady..

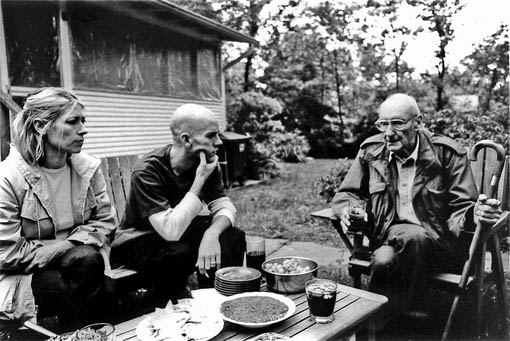

International Poetry Congress, London, 1965. Top Left: Barbara Rubiin. Back row L-R: Adrian Mitchell, Anselm Hollo, Marcus Field, Michael Horovitz, Ernst Jandl.

Front row: Harry Fainlight, Alex Troicchi, Allen Ginsberg, John Esam, Dan Richter. Photograph by John Hopkins

Trocchi’s detachment is unsettling; love, death, friendship at once fictional and real has lost the gravitas of experience or tragedy and devolved into passing anecdote. The mood flowing through this long warbling tapescript is confused; impotent in more ways than one. While Ginsburg seems intrigued and pitiful of Trocchi, Peter Orlovsky also present ridicules him. Perhaps Orlovsky believes Trocchi in his state of utter impotence in 1979 when this conversation took place had received his just desserts. Considering in his prime Trocchi not only was a great proponent of heroin as a pinnacle of unproductive creativity, getting many people around him hooked (it is said he taught William S Burroughs how to inject…), but he was also their drug dealer. Depending on your interpretation he is at once the instigator and supporter of these figures’ (including his wives, children, Mel Sabrum and “his one-legged girl”) transcendental escape; and/or their misery and death. Trocchi has appropriated and absorbed these people’s lives and deaths and regurgitated them into fiction; of reality he “drank and regurgitated, drank and regurgitated”. In swapping one for the other and vice versa and treating both with the same passing detachment the line between fiction and reality has not blurred, but disintegrated. They have become opaque, flat. Again, life and death; fiction and reality, all have become anecdotal. And literature too, everything Joe Necchi experiences is “like something out of Kafka”, or Beckett, his boat even, on which he writes, shoots up and drifts is the “Samuel B. Molroy”. Both Trocchi’s life and writing is intertextual; a malformed meeting of fiction and fact; neither concrete; neither authentic. Trocchi states that he is not writing fiction but “writing reality”:

I’m all the time aware it’s reality and not literature I’m engaged in

The act of writing for Trocchi is a spiralling saturating cannibalising diegesis.

In his talk cum

3:AM article cum Alma reprint of

Cain’s Book intro Tom McCarthy pinpoints Trocchi’s writing as between two points, a “white tundra” and a “black ocean”. McCarthy implies that the black ocean is the void of ink; heroin; nothingness, and the white tundra is the spatial nothingness of the city. In this interpretation Trocchi is writing for nothingness;

injecting for nothingness. He “wills to death”; straddling the precipice of existence; peering into both sides. However the act of writing, and Trocchi’s perception of heroin use as “another creative avenue”, strikes me as certainly productive; accumulative. If the white skin; the white page is a soulless void, then the heroin; the black ink is there to fill it. As John Cage states in his

Lecture on Nothing, “what we require is silence; but what silence requires is that I go on talking”. As Orlovsky says in their conversation, Trocchi cannot stop talking; he is caught in this paradox. He drifts between noise and silence; something and nothing; a vague ghost trapped amongst objects. The void that Trocchi strives to fill is not exterior, McCarthy rightly places it within him. It is interthoracic; within the belly of the monster. As Trocchi writes in

Cain’s Book: “a man who knows, speaks not; a man who speaks, knows not.” In writing at all, Trocchi is not writing to the edge of death but from it. He is productively searching for

something. Trocchi is not writing towards nothingness; he is writing to attempt to edify

something.

Before Trocchi’s forced resignation in 1963 from the Situationist International; Guy Debord thought of him as one of the finest representations of a drifter.

He’d bring me to a spot he’d found, and the place would begin to live. Some old, forgotten part of London. Then he’d reach back for a story, or a piece of history, as if he’d been born there … the flowerings of consciousness, the sudden comings together of space and architecture, knowledge and social interaction.

The drift is “to totality what psychoanalysis is to language”, it is the détournement of the Baudelairean flaneur and, again, Thomas De Quincey’s attempts to find “the north-west passage” in London. It is to treat the city as a found object, to be a detached traveller in the grime of the authentic proletarian milieu. And, as Guy Debord says, Alexander Trocchi was one of the best. This view of Trocchi as recuperator of the phenomenal world, set apart like De Quincey, by writing and opium consumption, provides a mode for understanding Trocchi beyond nihilism.

In Cain’s Book while Trocchi is boldly stating “there is no story to tell” and injecting his page-projection Joe Necchi with heaps of skag; below all that sliding away “like lava”; like facts below language; is what Trocchi styles becoming. Though the term in this context feels; rather than a constantly renewed being, more like being being perpetually pulled out from under him. In this it becomes apparent that the spatiotemporal soup his narrators slip through is not only the product of his search for situations to devour but mimetic of the fuddled narrative bent of a delirious mind. The phenomenal universe of Cain’s Book slips through Trocchi’s memories; through time and space. It devours and employs for narrative gain everything; New York; London; Glasgow; Paris; Hull—it takes the sum of his human interactions and in fictionalising them renders them devoid of real human contact. Time and again he laments with the refrain; “and with the ovens of Auschwitz scarcely cold”. Trocchi is carving up the past, present and future and regurgitating it into his own “eternally living will and testament”. Trocchi is not trying to disintegrate himself; he is attempting to disintegrate history. As the drifter he treats the universe, places, things and people, as found objects from which detached he harvests experiences; situations. It is in this Trocchi himself could be said to be inauthentically “I”; like Joe Taylor in Young Adam on the barge he isn’t a bargeman; he is just doing a bit of passing work; like the Situationist drifters of the down trodden quarters of Paris he is again, just a visitor. He is gaming. To think of “I” pointing to an essential humanity is to place it within the phenomenal universe, however Trocchi’s narrators and Trocchi himself is just passing through, he escapes interrelating objectification. In his detached harvesting of experience he is essentially a Situationist. And in regurgitating reality as inconsequential anecdote creates a field of confused interrelation below the concrete; he reduces the world to Tartarus. Trocchi’s writing does not dissolve like heroin in the spoon but eternalises his self as mixed up in a schizophrenic broken jigsaw universe; a chaotic world devoid of human authenticity. He attempts to break up his self and history and the real and wrap it up in the pages of his two “serious” novels. In his failed attempts to achieve ekstasis through writing and heroin, like the folly of Parc Monceau; his texts “unite in a single space all times and all places”. Trocchi is perpetually in the act of self-historicising and these novels are Trocchi’s forever “living will and testament”. He is again caught in the paradox of silence and noise, he desires to both disintegrate history and eternalise that disintegration.

To look back at the Ginsburg/Orlovsky tapescript

Peter Orlovsky: And you’d be talking all the time!

AT: What’s that?

Peter Orlovsky: Your lips are moving all the time..your tongue is up to your nose, your eyes are popping out your face.

AT: Well dammit, they should be! I don’t see you very often. Look, I’ve got things to talk to you about Allen, I really have, serious things, I mean really serious things..

Orlovsky conjures an image of Trocchi as Cain; this monster of noise overwhelming the silence of the exterior with his interior vitriol. It seems here whether Trocchi wished to disintegrate history or contribute to it, it has expanded around him; engulfed him. In his attempts to ingratiate himself with a newly fractured history he has inadvertently disintegrated his self. Like De Quincey, in striving to utilise opium as a tool of potent creativity he has rendered himself impotent. In Cain’s Book he writes that he would need a “new language” to communicate what Philip Toynbee called the hallucinatory new real world post-war. But like Fay in Cain’s Book in utilising heroin he does not will to nothing, but falls into the void within heroin magnifies. A more fitting “living will and testament” is perhaps Fay’s utterance towards the end of that book, “Dbaeioug eukuh…”; an incoherent mumble. Heroin has failed to materialise its artistic merits assigned; it seems more like Trocchi disguises his addiction as art, as Necchi hides his track marks by pretending to be an artist who paints with blood.

In his 1963 essay “Technique du coup du monde” in Situationiste International #8 Trocchi sets out a plan for a kind of potlatch city. A “spontaneous university” that; through requisitioning education would erupt into a new kind of urban object; it was his stab at unitary urbanism. He claims in the essay that by will of human unified individuality; “a million creative minds”; a new kind of modernity may be achieved outside commodity. By 1964; after his ejection from the SI; he came again to the idea in an essay on his new movement Sigma. In this he employs his “spontaneous university” concept in an utterly different manner; Sigma would function more as an eternally self-perpetuating literary agency co-op. Sigma the name itself implying that which it signifies is something eternal. Potlatch has been replaced here by the utilisation of celebrity and wealth to open up centres of teaching and interview and publication; for the sale and proliferation of his and other members’ products. His “spontaneous university” has moved from creative “invisible revolution” to a business model; he himself has commodified the concept. This shift correlates to that between Young Adam and Cain’s Book, and perhaps a wider shift in art. From agitprop to agency. For Trocchi from detached drifting to self-historicising in a mashed up pseudo-reality; the shift from creation to consumption; recreational to addiction.

Alexander Trocchi and his works seem caught in the inertia of addiction; not only to heroin but to literariness. Between the blank page and the heroin needle Trocchi is imprisoned. He is not detached but isolated. His drifting is not an aesthetic, it is a necessity. In this sense it is hard to see Trocchi as a nihilist; he appears to us as a ghost; a vaguely sketched outline of the post-war writer. He inhabits a hallucinatory reality; the world submerged in haze and chaos; he drifts in Tartarus, where both the real world and literature has disintegrated into the anecdotal. Rather than meet the ambiguous space he inhabits, the dosshouses, the rundown neighbourhoods, the scenes of death and decay; he attempts to escape them. In his detachment he refuses to interact and interpret them and thus relinquishes any claim to involved discourse with them. Alexander Trocchi is not a nihilist, he is the victim of a society that has shunned him. Due to his heroin use he has not detached himself from reality; but reality has detached itself from him. For Trocchi life and death; reality and fiction is one, a pile of ripped up jigsaw pieces. He does not straddle the tundra and the ocean; peering into both. The tundra and the ocean are his cell walls; his writing the ever quieter assertion of his freedom.