Cyberkampf

Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Muzak: An interview with Klaus Maeck

by Christophe Becker

Moi qui comptais déconner jusqu’à l’article de la mort. — Samuel Beckett, Eleutheria

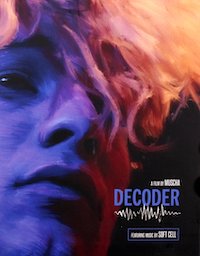

I never knew who Klaus Maeck was. Even when I was finishing my PhD on the influence of William S. Burroughs on William Gibson and Genesis P-Orridge in 2010. The man seemed to be completely off the radar. It took some time — and a great deal of luck — to stumble upon the movie Decoder he’d co-directed with Muscha, Volker Schäfer and Trini Trimpop. A movie starring non other than William S. Burroughs and Genesis P-Orridge. A wonderful film and a miracle of some sort.

Klaus Maeck, along with Muscha, Schäfer and Trimpop, used Burroughs’ sound theories and gleefully put them on screen. A cyberpunk world where revolutionaries and wild boys used sound to disturb the status quo, to fight the good fight and destroy the police state. This interview is part of a much longer work entitled “The Electronic Revolution will not be televised. Le « son Burroughs » dans le film Decoder (1984),” published this year.

Decoder is now available on DVD and Bluray thanks to Vinegar Syndrome.

Christophe Becker: What is your first memory of William S. Burroughs (as a reader, as an individual)?

Klaus Maeck: It was in the mid 1970s. I read some of his texts in American and German underground magazines like Gasolin 23. I was impressed by his view of the world, his language. Then the German publishers Udo Breger and Pociao published the book The Electronic Revolution — way ahead of the electronic revolution that was yet to come — with essays and manuals to interfere with mainstream structures… This was my bible for a time, together with Daniel Odier’s interview book The Job. I only read William Burroughs’ novels later and maybe I didn’t understand half of what he wrote. But somehow — I could feel it. That was quite a strong experience, to realize what language can do. That it can blow you away.

CB: Among the films you directed or produced, two of them involve William S. Burroughs: Decoder (1984) and Commissioner of Sewers (1991). Can you explain his impact on your work?

KM: Burroughs’ perspectives on society and art inspired me so much that I started to write and record and film and to cut it all up. At that time, we had quite violent encounters with the police and other state troops due to our resistance against nuclear powerplants and due to our furtive sympathy for German radicals like 2 June Movement or the Rote Armee Fraktion. What I decided was not to fight physically against the superior powers of global Goliaths but — if I wanted to change anything about the corrupt structures of Western civilization or at least make people aware of them — I would rather take the subtle way by using the new media options like tape recorders, video, and film. One of the ideas was the script for Decoder. And after a personal visit to Lawrence, Kansas, I asked Burroughs if he would play a small but kind of “key” role himself in my first feature film — which he luckily did. For a bottle of vodka.

CB: Can you explain why Muscha is credited as the sole director while you’re credited as producer?

KM: Easy: films almost always have one director. Although we started as a collective and produced this film together — from editing the script, preparing and filming and editing — there comes a point in time when you need a poster and credits. A film by four people? How can it work? Well, to be honest, it didn’t. Although we planned to do it all together Muscha was the one with a stronger visual concept and very soon after starting to shoot we accepted his role as a director. So the poster says. But I really see Decoder as a team work — as all films are! However, as I was the one who started the project and being today the only one left of that team to take care of this film, to keep it alive, I do see it as my film. Whatever — it’s a credit, I don’t care too much. I just care for the film, and I love the fact that it had a kind of revival over the last few years and people are curious to know more — like you.

CB: How was the title Decoder chosen?

KM: The working title of my script was “Burger Krieg.” A mixture of English and German and if you pronounce “Burger” as you do in English, it sounds very similar to the German word “Bürger” which means “citizen,” however “Bürgerkrieg” means “civil war.” After finishing the script we found a better name, we were not happy — too much “Burger” (H-Burger) in the title… Because the film really is about decoding muzak and other codes. Not sure anymore who came up with the name, but we all knew instantly it was our choice.

CB: When and where did you first meet Genesis P-Orridge and F. M. Einheit?

KM: F. M. Einheit was coming into my punk store Rip Off around 79/80, coming from provincial Bochum to Hamburg looking for action. He searched for a band which would be different from all the boring rock bands at the time — and found the musicians around Frank Z. — so they formed Abwärts, one of Hamburg’s first punk bands. Not much later we lived together — 6 people in a 6-room-commune in St. Pauli. My room was next to Frank Z.’s, then came F. M. Einheit, Christiane F., Anja Huwe from X Mal Deutschland and others. A commune of musicians, more or less. And when musician friends played in town — such as Einstürzende Neubauten or Psychic TV or others — they had a place to stay or sleep. That’s the way I met Genesis, in my room. I remember asking him why he would suggest wearing uniforms like they did at the time and following their rituals… and he said it was a game. Let’s see where it leads. Well, we saw… However, I told him about my idea for Decoder and that I would love him to play in it, actually he should play himself. A cult leader. He liked the idea and joined the project. In fact he helped us a lot. Organizing the location in London to shoot the scene with Burroughs during the Final Academy in Brixton, asking Sleazy to organize equipment and be the camera operator. And inventing his own dialogue lines which are maybe the most important in the film: “Information is like a bank. Some people are poor, some people are rich with information. We have to rob this bank…” — he said that when we filmed in winter 1982! How weird that I will use that excerpt from the film in my new documentary about the German hackers from Chaos Computer Club who are following and proposing this rule since then actually.

CB: Funny you should mention the Chaos Computer Club and hackers. A few years later Hans Hübner (Pengo) would be arrested in Germany. As a hacker he was influenced by William Gibson who is an avid Burroughs reader to this day.

KM: Well, well… Wasn’t he the one who called himself Hagbard Celine after the Illuminatus Trilogy by R. A. Wilson? Gibson and Burroughs — of course there is a connection — but I would not draw the line to Pengo and the CCC.

CB: How were the cast of Decoder chosen?

KM: As you can imagine from the above answer, we took it as it came. F. M. Einheit was living with us in St. Pauli, he just had joined Einstürzende Neubauten. He was the sound hacker par excellence. He only needed to play himself. Christiane F. lived with us, being a well-known book author at the time (Die Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo, 1978). She was clean at the time and looking for a place to start a new life. Her other identity was the famous junkie being written about and her book being made into a film starring David Bowie… She was in the press and at the same time looking for hideouts. That gave us the idea for her role in Decoder — she played the double identity of a peep show girl and someone who preferred frogs to humans.

More cast? Ralf Richter, the assistant of Bill Rice, is actually the brother of F. M. Einheit and a real actor. One of the few real actors in the film. And Bill Rice? This great off-theatre actor from New York we saw in the underground movies from NYC at the time, like Subway Riders and others. A movie by Amos Poe, photography by Johanna Heer, an Austrian camera director whose lighting was very special, very extreme, we all loved it. When we asked her to shoot and light our movie we also asked her to bring Bill Rice. And she did!

CB: What were the initial reactions at the Berlin Film Festival in Feb., 1984?

KM: Not good. The reviews were bad — the film critics did not understand (easy to say now)… Surely it was a very non-conventional film, not having a straight storyline. Or one which was not easy to follow. We ourselves realized at that point that making a film with four people (who all wanted to have a say, who all wanted to put in their ideas) was not the best idea. We could have made four films out of it, maybe. Anyway, because of this poor reaction we didn’t find a distributor and got stuck, there was no cinema release until 1986. And that only happened because I found a one-man-distribution-company in Berlin and this guy was smart. We applied for more funding to support the distribution for the film, and with this money he engaged and paid me for some months to promote the film and organize cinemas to play Decoder for a week. It did not go well though, but as I already realized international festivals were interested in the film. People in Milan, Los Angeles and elsewhere organized screenings, I was happy that the film had at least some impact outside of Germany. Especially in Italy, the USA and Japan, weird, isn’t it?

CB: You use Burroughs’ voice as taken from Nothing Here Now But The Recordings (1959-1980). What was your reaction to the record?

KM: I loved it!

CB: Did Burroughs’ work and theories change your way of filming and editing? Were you familiar at the time with Antony Balch’s work like Towers Open Fire (1964)? If so, did it influence the shooting and / or editing of Decoder?

KM: Yes, I knew all these films. As I mentioned before, I experimented a lot with cutting up film and sound, but I wasn’t happy with the results — at least not for a wider audience. Of course, Burroughs’ and Balch’s work influenced the way of editing the film — and before that in editing and writing the script in a non-linear way. You see what critics thought of that, see above. However, we were quite happy with the result and also the effects of the film when it came out. We only wished that more people would understand what it was all about. After that experience I decided to try and make more approachable films rather than pieces of art.

CB: Music and riots seem to pop up frequently in your work. New Order’s Singularity video co-directed with Jörg A. Hoppe and Heiko Lange comes to mind.

KM: The film B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West-Berlin 1979-1989 was written, produced and directed by Jörg A. Hoppe and Heiko Lange and myself and — simple answer — we used excerpts of Decoder. And the New Order video used excerpts of B-Movie!

The Contributors

Klaus Maeck was born on July, 28, 1954, Hamburg, Germany. He’s a producer, script-writer and director. He co-directed Decoder in 1984 and directed the documentary William S. Burroughs: Commissioner of Sewers in 1991. Among his other movies: Liebeslieder: Einstürzende Neubauten (1993) and B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West-Berlin 1979-1989 (2015).

Christophe Becker was born on October, 16, 1975, Paris, France. After a Phd on the influence of William S. Burroughs on William Gibson and Genesis P-Orridge, he now works on experimental literature, science-fiction (Karel Čapek, Kurt Vonnegut, William Gibson) and the French punk scene.

Acknowlegements

Klaus Maeck for being so patient, Clémentine Hougue, Noëlle Batt, Oliver Harris, Peggy Pacini

- View original post