środa, 28 maja 2025

poniedziałek, 12 maja 2025

Bad Reputation [Dokumentalny] (2018) Napisy ENG /PL

Bad Reputation [Dokumentalny] (2018) reż. Kevin Kerslake [Napisy ENG /PL]

poniedziałek, 7 kwietnia 2025

The Exploited and the Crossover Era (1986-1989)

The Exploited and the Crossover Era (1986-1989)

An Interview with 'Deptford' John Armitage

Best known as the bassist of the Oi! band, Combat 84, 'Deptford' John Armitage was a cult figure within the early-'80s skinhead scene. Though never formally affiliated with the RAC (Rock Against Communism) movement, Combat 84 certainly flirted with the harsher stances on the punk political spectrum. They arrogantly walked a thin line that subsequently would see them championed by the right wing side of the Oi! movement. In 1984, Germany's infamous Rock-O-Rama Records, the once-punk-turned-fascist label would release what became Combat 84's sole LP, "Send In The Marines!" This release was later disavowed by the band as an unofficial release, however the repetitional damage had been done. Combat 84 attempted to continue to gig under the name pseudonym The 7th Cavalry, but it was short-lived, and the band broke up.

This enigmatic lore, coupled with his rumored leanings towards the dodgier side of politics understandably served as fodder for many urban legends about the man and his associations in the pre-internet era. John has since made multiple statements over the years regarding his time with Combat 84, opposing any such personal endorsement of the ideas that his name had ultimately become associated with through that period of his life.

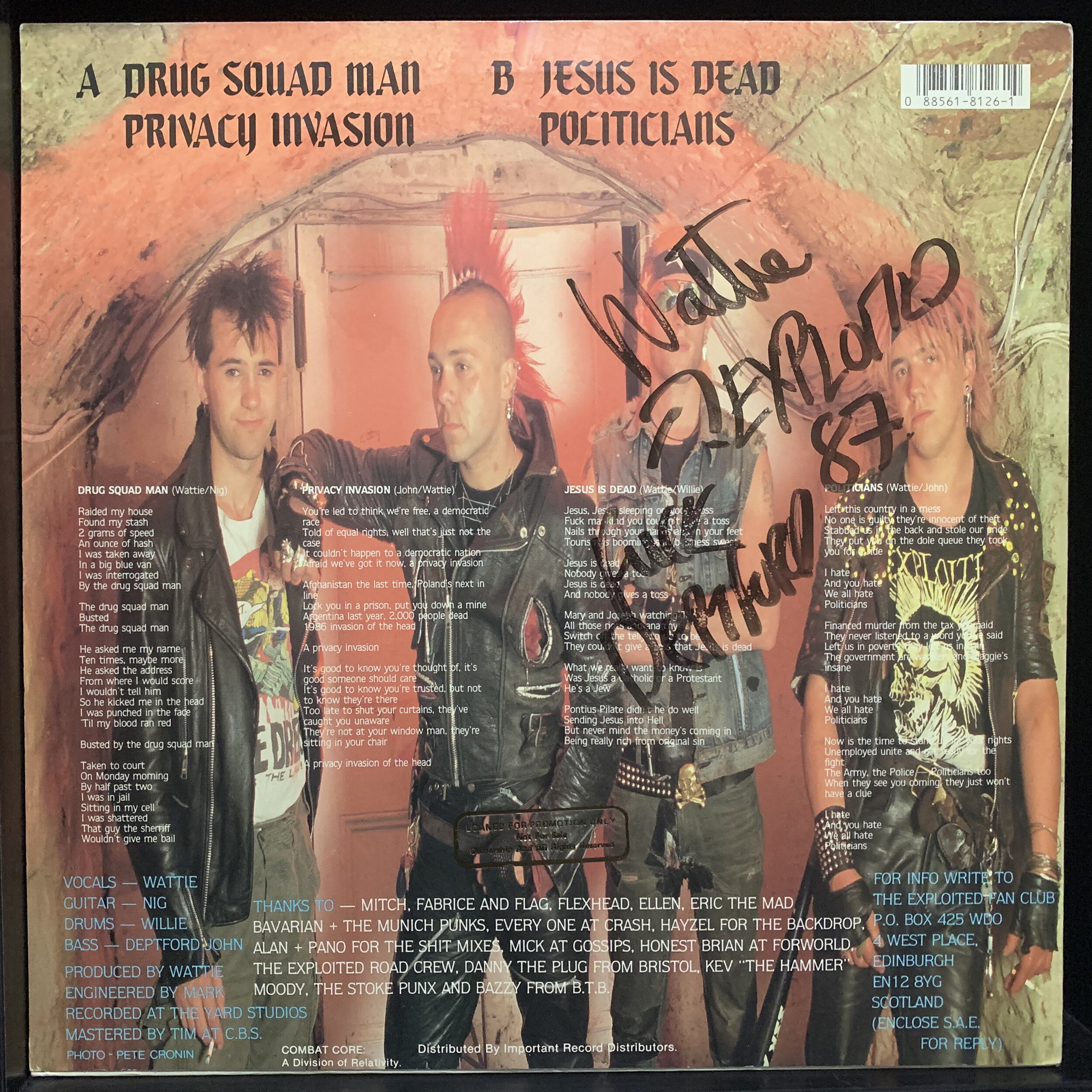

Though Combat 84 would remain the focal point of John's résumé for years, his career would go on to span far beyond that. He briefly joined the U.K. Subs in the mid-'80s, appearing on the "We Don't Want Your Fucking War!" comp LP released by Conflict's label Fight Back Records in 1984 as well as the "This Gun Says" single released by Fallout Records in 1985. Upon exiting the U.K. Subs, John joined The Exploited for the "Jesus Is Dead" EP from 1986 (Rough Justice).

This EP was a turning point in the Exploited's sound, as they moved toward the faster and harder crossover sound that was gaining in popularity at the time in the mid to late 1980s. The UK82 wave had died out, and just about everyone was moving toward incorporating a metallic crunch in their sound. The Exploited had been heading in a harder and faster direction since their inception, and 1983's "Rival Leaders" EP for Pax Records was one of the hardest records of the era to come out of the United Kingdom.

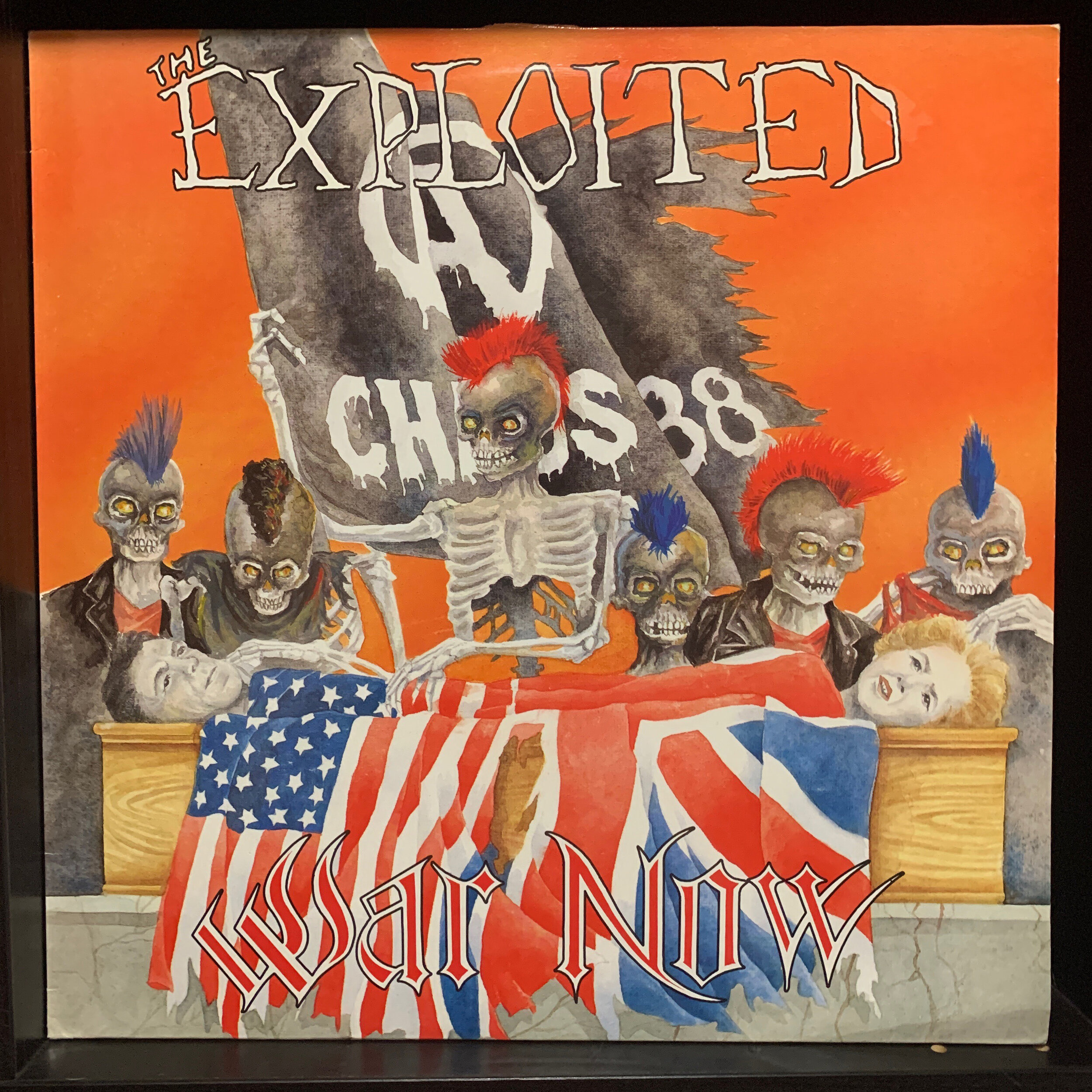

But it was a trio of releases from the second half of the decade that brought The Exploited name to an entirely new subset of fans. The aforementioned "Jesus Is Dead" EP (1986), "Death Before Dishonour" LP (1987), and "War Now" EP (1988) saw The Exploited not only move into the crossover genre, but stake their claim as one of the elites of it as well. While the band always had a driving edge to their sound, these songs were blazers and bangers, full of searing riffs accented perfectly with Wattie's unmistakable bark. They were all released by Rough Justice in the U.K. and Combat/Combat Core in the United States, which were two of the premier crossover labels at the time and also home base for GBH, Broken Bones, English Dogs, Agnostic Front, Crumbsuckers, Corrosion Of Conformity, The Accüsed and more.

This era's lineup featured Wattie on vocals, Nigel 'Nig' Swanson on guitar, Willie (Wattie's brother) on drums, and a different bassist on each release (Deptford John Armitage, James Anthony Thomson Lochiel AKA Tony, and Mark 'Smeeks' Smellie, respectively).

In this interview, Deptford John discusses his time in The Exploited, the "Jesus Is Dead" EP, plus a couple surprises. John would later go on to become a renowned guitar tech and repair man, working for Iron Maiden (on the Killer Crew from the 1990s through the early 2000s) and many more, which is how he currently makes a living today.

You came to join the Exploited a short time after being in the U.K. Subs. Why'd you decide to leave the Subs?

I didn’t decide to leave the Subs; they fired me!

Was the "This Gun Says" single the only U.K. Subs release you recorded for?

With the Subs, I recorded a track called "Anti-Warfare" or something like that for a compilation album called "We Don't Want Your Fucking War!," I think. That's all I can remember!

Was it a big musical shift going from Combat 84 and U.K. Subs to the more hardcore sound the Exploited has at the time?

It wasn't a big musical shift as I was already getting into hardcore and crossover music at that time and thought the Subs a bit too R&B for the current climate at that time.

With you being from London, how did you end up joining the Exploited? Had you been a fan of them prior?

The two bands had just done a co-headline tour of the USA, and I knew the bass player was going to leave after the tour. So when the Subs sacked me, I rang Wattie and offered my services.

Had you known Wattie and those guys a while?

I'd known Wattie and Willie a couple of years by then.

Did you join as a full member or were you filling in?

Joined as a full member, did about 18 months.

Shortly after joining you went on a tour with them in Europe. Was this your first time on an extensive tour?

No, I'd been a tech for the Subs before I joined and had worked for other bands too.

Did you enjoy it, and what was the crowd reaction, as the band were huge at that time?

It was a great laugh, shared a room, drugs and parties with Wattie. It wasn't that much of an upgrade crowds wise in most areas though.

Is there any particular events that stick out from the tour?

Went to Yugoslavia for the first time, more women went to see the Exploited too.

The lone studio recording you play on is the "Jesus Is Dead" EP. Were you involved in the writing process of it?

Yes, I was, and in securing the publishing deal.

What are your impressions of the EP?

Not too bad, was an initial release for the label so had to play it a bit safe.

Coming out of Combat 84 and U.K. Subs, were you into the direction the Exploited were going musically, which was harder and faster and moving toward the crossover style?

It was what I wanted to play, but the drummer in the Subs wasn't up to it! Very happy to move into that style at that time.

Any memories of Nigel Swanson as a guitarist and what he brought? Did you like working with him? Did you write with him? He took The Exploited in that crossover direction quite well.

I liked working with Nig, but we had different styles as musicians. I was more into the hardcore side and he was more into metal. He introduced me to some great bands, but it wasn't the style of stuff I wanted to play so we were both constantly compromising. He was a good bloke though, and was becoming a decent player whereas I was losing interest in playing in a band where the rehearsals were 450 miles from where I lived.

Were you involved in writing any of the songs that appeared on 1987's "Death Before Dishonour" album?

Yes, I wrote three or four, but Wattie registered them as his. "War Now" was all me!

What made you decide to leave the Exploited? Was it a difficult decision?

All the money went to Wattie and we couldn't get a decent guitar player to stay, so I felt I was treading water. Also I was getting more money as a tech with bigger bands and could see a better future for myself if I went back to teching as my main job.

Any final thoughts on your involvement in the band or other things to add?

I loved being in all three bands. They all turned out to be stepping stones to where I wanted to be. I've worked for the biggest bands in the world (check out my bio) but still love punk and Oi and hardcore, as I never tried to make a living out of it!!

poniedziałek, 17 lutego 2025

Około Północy [Round Midnight] (1986) Napisy ENG/PL

Około Północy [Round Midnight] (1986) reż. Bertrand Tavernier [Napisy ENG /PL]

poniedziałek, 10 lutego 2025

The untold story of forgotten UK reggae heroes The Cimarons.

‘The way they’ve been exploited is obscene’: the untold story of forgotten UK reggae heroes Cimarons

Download "Projekt UFO" (2025) miniserial PL

Projekt UFO (2025) miniserial PL Próżny prezenter telewizyjny i ufolog z małego miasteczka próbują odkryć pochodzenie...

-

Save folder [435A07E0] move to Xenia Canary folder [content] Instant Brain (Xbox 360): Download...

-

Projekt UFO (2025) miniserial PL Próżny prezenter telewizyjny i ufolog z małego miasteczka próbują odkryć pochodzenie...

Moja lista blogów

Obserwatorzy

Szukaj na tym blogu

O mnie

Archiwum bloga

-

▼

2025

(5)

- ► kwietnia 2025 (1)

- ► lutego 2025 (2)

-

►

2024

(7)

- ► czerwca 2024 (3)

- ► kwietnia 2024 (2)

- ► marca 2024 (1)

- ► stycznia 2024 (1)

-

►

2023

(7)

- ► listopada 2023 (1)

- ► października 2023 (4)

- ► sierpnia 2023 (1)

- ► stycznia 2023 (1)

-

►

2022

(19)

- ► października 2022 (2)

- ► lipca 2022 (1)

- ► lutego 2022 (15)

- ► stycznia 2022 (1)

-

►

2021

(8)

- ► listopada 2021 (1)

- ► czerwca 2021 (3)

- ► marca 2021 (2)

- ► stycznia 2021 (2)

-

►

2020

(23)

- ► grudnia 2020 (1)

- ► października 2020 (2)

- ► września 2020 (1)

- ► sierpnia 2020 (2)

- ► lipca 2020 (2)

- ► kwietnia 2020 (1)

- ► marca 2020 (3)

- ► lutego 2020 (4)

- ► stycznia 2020 (6)

-

►

2019

(34)

- ► grudnia 2019 (28)

- ► września 2019 (1)

- ► lipca 2019 (1)

- ► kwietnia 2019 (1)